Amal N. Ghazal, Islamic Reform and Arab Nationalism: Expanding the Crescent from the Mediterranean to the Indian Ocean (1880s-1930s). New York: Routledge, 2010.

Jadaliyya: What made you write this book?

Amal Ghazal: I wanted to find a topic that bridged my two fields of study, Middle East Studies and African Studies. I thought Omani rule in East Africa would be interesting, especially in that I was initially able to trace correspondence between Arabs in East Africa and newspapers in the Middle East. A research trip to Oman revealed that I was stepping into a goldmine: Omanis in Zanzibar were deeply connected to political and intellectual networks throughout the Middle East and North Africa and were part and parcel of the movements of Arab nahda, religious reform, and later on, Arab nationalism. Archival material, newspapers, private correspondence, and manuscripts, collected from Oman, Zanzibar, Algeria, Tunisia, Syria, Lebanon, and England, were used to put this project together. I was fascinated by the material I was digging up and was delighted by the opportunity to visit Ibadi communities and become familiar with the all but forgotten sect of Islam, Ibadism.

Jadaliyya: What particular topics, issues, and literatures does it address?

AG: The book argues that segmented accounts of identity politics and nationalism in the Arab world do not provide a clear picture how Arab intellectuals at the turn of the twentieth century developed their ideas. I look at how local discourses of identity politics, especially under European colonialism, were shaped through wide networks of connections, and I take the Omani intelligentsia in Zanzibar as an example. Since almost all Omani intellectuals on the island were of the Ibadi sect, the book deals with Ibadism and its intellectual history in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. In particular, I analyze the political and intellectual contexts that led to a rapprochement between Ibadis and Sunnis and the implications on nationalist thought. I have two chapters on the interwar period that contain a discussion of the rise of Arab nationalism on the island and the definition of Zanzibar as Arab and a member of the Arab world. As you can imagine, the book addresses a whole set of literatures: disciplinary boundaries that cut off the intellectual genealogy of Arab history, one that I reconstructed by bridging the two fields of Middle East and African Studies; Islam in Africa; Omani rule in East Africa; Ibadism and its place in the field of Islamic studies; the different meanings of “resistance” to colonialism; and the scope of Arab nationalism and of religious reform.

[A tarab band performing in Zanzibar in 2011. Photo by Amal Ghazal.]

Jadaliyya: How does this work connect to and/or depart from your previous research and writing?

AG: On the one hand, it is a major departure. I wrote my MA thesis on the Sufi conservative anti-reform thought in the late Ottoman period, represented by the writings of Yusuf al-Nabhani. At the doctoral level, I developed an interest in African history and the historiography of Islam in Africa and wanted to do something completely new. On the other hand, it is my background in Middle Eastern history and my interest in the late Ottoman period and the transition into a post-Ottoman order that helped me to understand the broader dynamics of the topic. The overlap between the two projects of research consisted mostly of debates about religious reform that I traced in Oman, Zanzibar, Algeria, and Tunisia. But I must add here that the switch from one project to another and the training in those two fields of study has helped me to better identify my role as a historian. I am constantly asked whether my work on Zanzibar identifies me as a historian of the Middle East or of Africa. The aim of the project is to show how those disciplinary divisions I am supposed to adhere to can be damaging to our research methodologies. My answer is that I am a historian of the Arab world. I follow its borders wherever they expand.

Jadaliyya: Who do you hope will read this book, and what sort of impact would you like it to have?

AG: I have three audiences: one that is interested in the Arab world generally speaking, one in the field of African history, and one in Islamic studies. In terms of impact, the book widens the scope of modern Arab history by integrating the Omani rule in East Africa; brings to the forefront of academic discussions the overlooked role of the Ibadi communities in movements of anti-colonialism, reform, and nationalism; and pushes us to reconsider the relationship between religious reform and nationalism in the Arab world. I really want to give Zanzibar its proper place in Arab historiography, given not only the intellectual connections and political ties to the Arab world but also the financial contributions offered by Omani sultans in Zanzibar to the pioneers of the Arab nahda. When I was in Oman talking to Omanis from Zanzibar, I often heard them refer to Zanzibar as the other Andalus that Arabs lost. As a historian of the Arab world, I was intrigued, and aimed to analyze how Zanzibar came to be considered as such and also how it came to be forgotten by most Arabs.

[Amal Ghazal. Image via the author.]

Jadaliyya: What other projects are you working on now?

AG: My previous work has led me to further research the relationship between Salafi modernist Islam and the rise of nationalism in the interwar period, both territorial and Arab nationalisms. By looking at the activities of Ibadi Algerians in interwar Tunisia, I want to revisit three sets of historiography: the (dis)connection between religious thought and nationalism in the Arab world; the origins of Algerian nationalism; and the methodologies of studying nationalist thought. I am looking at the network as an analytical tool, rather than individuals or classes, to chart the development of nationalist movements. I am very excited about this new project, which has received funding from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (Canada).

And when in need of a diversion, I go back to my earlier work on the Sufi anti-reform movement in the Hamidien period, which I have been researching further; I am hoping to ultimately write a book on the history of Sufism and of religious conservatism in the Arab provinces in the late Ottoman period. There is still much to be known about both the Arab provinces under Ottoman rule and about Sufism in the modern period.

Excerpt from Amal N. Ghazal, Islamic Reform and Arab Nationalism: Expanding the Crescent from the Mediterranean to the Indian Ocean (1880s-1930s)

Time and again, al-Falaq [newspaper] pulled Zanzibar into the heart of Arab-Islamic history and into the heart of Arab anti-colonial struggle, and time and again al-Falaq invoked past scenes of “Arab heroism” to venerate Zanzibar’s membership in that world. For example, in July 1939, an article was published commemorating the nineteenth anniversary of the famous battle of Maysalun, when Yusuf al-`Azmeh tried to defend Damascus against advancing French troops.

Dear Reader,

Today, while you hold this newspaper in your hands, and you look at its contents with your eyes, is the 19th anniversary of revolutions led by Arab freedom fighters…

Because you are an Arab, Maysalun is an Arab tragedy, al-Falaq is an Arab newspaper, and because I am an Arab, I should tell you about Maysalun and its tragedy that fell on all Arabs…[1]

The long journey that separated Damascus from Zanzibar and the years between 1921 and 1939 could not render Maysalun meaningless to al-Falaq’s readers. Distance and time were shortened by a collective history that was recreated and reconstructed to project a collective identity and a collective tragedy brought by colonialism. Maysalun was a memory to be shared and a tragedy to be commemorated by all Arabs, including those in Zanzibar. This collectivity could also be seen as a power to reckon with and thus, al-Falaq was prompted to warn Europeans on the eve of World War II that the era of enslaving Arabs was over. “It was time Europe realized,” al-Falaq announced, “that each Arab or Muslim looked askance at it because of its harsh and inhuman treatment of the descendants of the Arabian Peninsula.”[2] Al-Falaq drew the attention of its readers to all the agitation and protest taking place in Iraq, Syria, Palestine, Egypt and the Arabian Peninsula as signs of Arab rejection of enslavement. Al-Maskari in his turn also called upon all Arabs to decide their fate by themselves and not to trust any European country, whether it was an enemy or claimed to be a friend.

They [Arabs] shouldn’t trust any promise in the future after they had seen the results of previous ones. They desire nothing but to live freely in their own countries like others do… Beware Arabs and Muslims of European propaganda broadcasted daily. It is all colonial deception… Move ahead Arabs and defend your rights and your countries.[3]

Europeans were driven by their greed, he added, and their inter-rivalry was only for the sake of executing their schemes to control Arabs and Muslims. If anyone was in doubt, al-Maskari pointed to French policy in Syria and British policy in Palestine. “The best proof is what the French authority is doing in Syria in terms of savage acts and what the British authority is doing to Palestinians.[4]

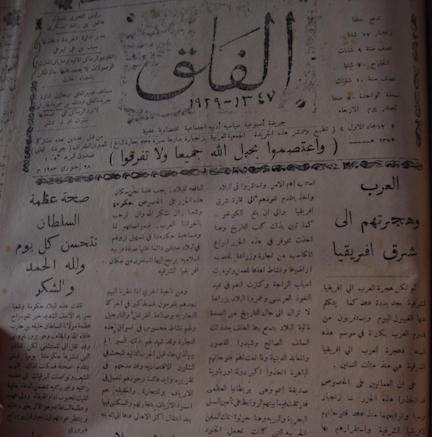

[Al-Falaq newspaper, first published in Zanzibar in 1919

by the Arab Association. Image via the author.]

Palestine and the Palestinians loomed large in the consciousness of Arabs in Zanzibar, as they did in the whole Arab world in the 1930s, especially after 1936. Palestine was the Arab issue without rival and one that galvanized and emboldened all discourses of Arab unity and anti-colonialism. In the words of one author, “the one issue that consistently found an echo among the urban, educated Arabic-speaking populations of the Middle East was the increasing danger of Jewish immigration into Palestine. Here was a concern that would unite the Arab nationalist, the Islamist, and the believer in Greater Syria…”[5]

The echo reached Zanzibar whose Omani intelligentsia was marching to the beat of the Arab world and was as concerned about Palestine as all other Arabs and Muslims were. The Arab revolt in Palestine (1936-1939) forced cooperation not only between Arabs but also among Arab governments and highlighted the plight of Palestinians as that of “Arab brothers” battling colonialism.[6] Their plight met with extensive coverage on the pages of al-Falaq that reported incessantly, after 1936, on events, activities, and news related to the Palestinian issue.[7] It reprinted articles from other journals, published statements and announcements by a number of Arab associations dedicated to help the Palestinians and offered news analysis of what the Palestinian situation implied for Palestinians and for Arabs. Abu al-Barakat (a pseudonym for al-Lamki), for example, commented that the reason Britain was handing Palestine over to the Jews was because it did not want two Arab governments formed on the borders of the Suez Canal. England knew “who Arabs were and it recognized through King Fayṣal and other Arab politicians such as Zaghlul to what degree an Arab can tolerate to be ruled [by colonizers]… Britain knows very well that an alliance with Arabs can be trusted as long as the Arab government is weak.”[8]

Notes

[1] Al-Falaq, July 22, 1939: 3.

[2] Ibid., April 8, 1939: 1.

[3] Ibid, May 27, 1939: 3.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Adeed Dawisha, Arab Nationalism in the Twentieth Century: From Triumph to Despair (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2005), 108.

[6] Ibid., 75-106.

[7] For example, al-Falaq used to publish all reports and statements made by the Arab Higher Committee.

[8] Al-Falaq, May 21, 1938: 2.

[Excerpted from Amal N. Ghazal, Islamic Reform and Arab Nationalism: Expanding the Crescent from the Mediterranean to the Indian Ocean (1880s-1930s). @ 2010 Amal N. Ghazal. Reprinted by permission of the author. For more information, or to purchase the book, click here.]

![[Cover of Amal N. Ghazal, \"Islamic Reform and Arab Nationalism\"]](https://kms.jadaliyya.com/Images/357x383xo/ghazal.jpg)